Online Editions

Third Folio, 1664 (ISE)

Fourth Folio, 1685 (ISE)

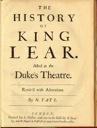

Tate, 1681 (SCETI)

Rowe, 1709 (Google)

Pope, 1723 (SCETI)

Theobald, 1733 (Google)

Wharburton, 1747 (Google)

Johnson, 1765 (Google)

Capell, 1767 (Archive.org)

|

A Third More Opulent: Digital Tactics for Expanding Lear

1. Provocations

This site arose from two provocations: a few compelling suggestions in Michael Best’s “Standing in Rich Place: Electrifying the Multiple-Text Edition or, Every Text is Multiple,” and a seemingly simple classroom assignment in gathering historical records around variant passages in King Lear. Returning to Best in a moment, we can begin by outlining the useful pedagogical exercise coordinated by Zachary Lesser at the University of Pennsylvania. Locating a single variant passage in Lear, we were to trace the various eighteenth and nineteenth century editions for collation data and editorial decisions. Armed with Folio and Quarto PDFs of Lear, and since most subsequent editions can be found online, this could remain a strictly digital task, with the caveat that we’d probably want to start with the textual notes in whichever conflated print edition we were working with.[1] The results of this textual gathering were superb — highlighting change and stasis in textual cruxes over three hundred years of varied textual processes — even while the process proved impossibly labyrinthine. The challenges and rewards of this exercise generated the impulse to consider the potential for a richer digital edition of Lear. Despite the overwhelming databank of HTML, PDF, Google Books, and other Internet editions of “Works” organized by “Shakespeare’s Editors” as coordinated by Terry A. Gray at the excellent Mr. Shakespeare and the Internet website, the labyrinth of historical editions of Lear online remained only minimally navigable. This may sound catty, just a decade into a time when works are expected to be instantly accessible on the internet when for centuries this kind of comparative research was simply impossible, or demanded extensive travel and archival research. Nevertheless, searching for these documents led me to wonder, why is the data so disorganized? In a field of immaculate collation, where is the digital variorum? An internet edition of this variety would not be particularly difficult to cull from the elements already out there, where are they and why don’t they yet exist? While literature and the arts are increasingly moving toward a fluid text aesthetic of data management, broadly characterized as remix culture, where are the efforts to coordinate the huge amounts of Shakespeare online into something more useful, with a concerted aesthetic of presentation at that? We’ll return to these questions in a moment, but first, the second provocation for an expanded Lear: Michael Best’s call to “electrify the multiple-text edition.” Best’s manifesto for electronic texts opens with a taxonomy borrowed from W. Speed Hill’s excellent article “Where We Are and How We Got Here: Editing after Poststructuralism,” worth recounting here. Added to traditional editorial publications that produce conflations, reprints, or copy-text editions are five additional strategies available to the contemporary editor:

1. Multiple-version editions (‘deconflations’ that provide several versions) 2. “Socialized” editions (following Jerome McGann’s Rossetti archive) 3. Hypertext editions (already “dazzlingly inaccurate” in a web 2.0 environment) 4. Genetic editions (which are of course impossible with Shakespeare) 5. No editions at all (focusing on facsimile editions after Randall McLeod, et al.).[2]

Effectively, however, the editor’s domain is split in two: between the impulse to “un-edit,” “deconflate,” and “reproduce” and the charge to “emend,” “conflate,” and “recompose” — with any variation of uneasy passage between the two. This dilemma holds for both electronic and print editions. What I’ll argue for here, as the title suggests, is “a third [strategy] more opulent.” Like Nahum Tate in 1681, we’ll consider how the tragic rending of Lear into facsimile or conflation may be mended with more creative editorial interventions enabled by information-dense digital formats and new aesthetic trends in electronic writing. Rather than cast off ‘inferior’ historical editions and free internet conflations, we can seek more robust forms of reading practices facilitated by networked digital formats. Best’s article goes on to demonstrate a few such possibilities for digital editions. The primary suggestion calls for a digital edition augmented by animated text to present the multiple. Whimsical suggestions for “mischievous” and “irreverent” editorial interventions include fading through the famous crux in Macbeth “weyard/weyward/weird/wayward” to cycle between all possible options, highlighting the text’s “actual instability, hidden by our meticulously edited print texts” or similarly bouncing the stage direction “Bottome awakes. Exit Lovers.” to its modernized inversion in Midsummer Night’s Dream.[3] The text thus literally animates irresolvable cruxes to amplify the impossibility of editorial fixity, proposing a solution to the editorial impasse explored by Margreta de Grazia and Peter Stallybrass in “The Materiality of the Shakespearean Text.”[4] Taken together these new media actions within the text are argued to open a critical space “exploratory and multifarious rather than declamatory and linear,” actively highlighting the variation so clearly present in footnotes from paper to paper and edition to edition.[5] It is surprising that these simple — and unseemly — actions are the solutions Best imagines for an environment that presents so many challenges to editors working with electronic media.[6] Before outlining potential digital interventions, Best himself compiles an excellent short list of new media editorial difficulties as follows: “how to assemble and manage the vast amounts of data that can be assembled for the edition; how to integrate multimedia annotations into the textual commentary; where to delineate the edges of an enterprise that can clearly become endless; how to develop a new semiotic of the screen, … [as the] quite complex printed page have become second nature to the reader… [and finally] the need to ensure that the standards of a traditional print edition are maintained in a medium that is at present associated with transience and rapid change.”[7] Without the readymade institutional credentials and long-established mores of print practices, preparing a digital edition is already compromised by these and other challenges such as attracting the attention of a serious reading audience while producing useful scholarly editions. Indeed, Andrew Murphy takes Best’s Internet Shakespeare Editions to task on several of these points, especially the last. Nevertheless the most successful of online editions outlined in “Shakespeare Goes Digital: Three Open Internet Editions,” Murphy applauds Best’s current project for its peer reviewed editions, modernized and transcribed copy texts, in depth collation data, and accessible facsimile interface. In Murphy’s view the “Internet Shakespeare Editions presents a vision of what editors can now do with the electronic text—provide scholars with something that really goes beyond the limits of the print edition.”[8] David Bevington’s edition of As You Like It, provides the most advanced demonstration of the proposed Internet Shakespeare Editions model. Fully collated and annotated according to the site’s stated aims, with particular strengths in pop-up annotations and a color-coded system for displaying textual variants, this is a great digital edition. And yet, this mechanism — functioning at its best — still misses a vast realm of immediately accessible functionality, in terms of available data, contemporary reference, and reading format. Murphy discusses these problems in terms of a distribution model introduced in 1853 by J.O. Halliwell-Phillipps that presented a luxurious and prohibitively expensive folio publication of Shakespeare’s works alongside a shilling edition for the masses. Murphy compares deluxe CD-Rom and print publications to impoverished Internet editions such as Open Source Shakespeare (derived from the widely available Globe edition first published in 1866, he notes “the reasons for choosing this text appear to be lost in the mists of prehistoric digital time”) and Shakespeare’s Words (similarly dependent on dated New Penguin editions with little-to-no editorial apparatus).[9] In contrast to Best’s optimistic vision for emerging electronic editions, Murphy concludes: “Does this mean that if we want a fully usable electronic text of Shakespeare we must wait for the latest incarnations of the big scholarly editions to be released in electronic form and probably have to pay for access to them?...For scholars, the answer may well be ‘yes.’”[10] Nevertheless, I must add, Murphy contends that the general reading public will continue to be content with ‘shilling’ editions lacking ‘textual niceties.’ Be this as it may, a third possibility remains: an open internet edition with an approachable aesthetic that presents valuable — and freely available — resources for researchers.

2. Abstractions It is at this point that the model proposed by Expanding Lear enters the conversation. Admittedly, the proposed site comes from an amateur in the field of Shakespearean textual studies, however, I hope it may present some pertinent ideas from the perspective of a programmer and archivist primarily concerned with relevant parallel disciplines including new media poetics, data visualization, and archival representation. While the site directly addresses ‘Shakespeare gone digital,’ its argument expands to a wider body of textual artifacts that might benefit from this murky realm of textual studies. This site thus presents an experiment in the field, answering Best’s call in a practical exercise, while considering potential qualities of rich digital editions — a third more opulent — in general. Simply stated, the site aims to present an engaging format for linear reading practices that can simultaneously expand to include a robust network of available resources that highlight textual mutability and provide easy inroads to a relevant multiple text experience for both popular and professional readers. A question of information density, this endeavor attempts to mix the various data streams related to Lear already universally available elsewhere on the internet. Thus, to the various modes of editions outlined by Hill above, it adds the dominant mode of contemporary cultural production on the internet, something we may term an editorial ‘remix.’ The remix might be problematically compared to the conflated text in that it is most interested in bringing a variety of already extant materials into play. However, concurrent with trends in deconflation, unediting, and socialized editions, it simply presents editions already trafficking rather than attempting to conflate a new text on a word-by-word level. Instead, it seeks to present a multiplicity of editions in a compact and accessible format. Emendation is reconfigured as a question of design. The single edition is replaced by an aggregator of textual resources. The ‘new’ simply presents what’s already there, newly arranged for the benefit of the user, who may easily navigate a rich array of source texts without losing sight of the narrative movement of the text. The challenge is to gather the abundance of available resources in a manageable reading interface — with various arrangements customizable by the reader. While this may sound a great deal like user-by-user eclectic editing, it operates on a larger scale, with less intervention and an in-built ideology of reuse and copyright that extends beyond the scope of this introduction. As the epigraph signaled, at this argument’s core is a new aesthetic of conceptual writing, best affirmed by Kenneth Goldsmith in 2004: “It seems an appropriate response to a new condition in writing today: faced with an unprecedented amount of available text, the problem is not needing to write more of it; instead, we must learn to negotiate the vast quantity that exists.”[11] This site argues that instead of editing a new text, a great internet edition can be formed from what’s already out there, in the various derelict editions, amateur collections, user-generated content, public domain sources, and cross-platform archives of all varieties. 3. Operations Before straying too far into theoretical abstractions, we can take this opportunity to outline the precise structure of the site and its various goals, properties, and potentials. The defining characteristic of Expanding Lear is a nested jQuery dropdown script that allows for textual notes to become invisibly enfolded into the text — thus within every line, collation data and commentary may be embedded and thus evaluated instantly. In the current version, I’ve included Q1 and F modern-spelling transcriptions below the Moby Shakespeare conflation for reasons I’ll discuss in a moment. While this is the present structure, a wealth of critical commentary, annotation, and collation data already widely available online ought to be inserted into these dropdown accordion fields in a series of layers tracking as deep as the reader would like to go.[12] A prominent example of this sort of depth may be found in Bernice Kliman’s staggering new variorum, The Enfolded Hamlet, perhaps the single most expansive (internet) edition of a work by Shakespeare — which has shaped this site both in terms of its failings and successes. Where the The Enfolded Hamlet codes material and immaterial variants by color and bracket, Expanding Lear presents a clean reading copy continuously available for deeper reading practices. Even for a professional researcher, the dominant mode (from ISE to TEH) of scrolling through pages, clicking through hyperlinks, and reading through idiosyncratic mark-up systems presents a significant challenge to reading practices.[13] At base, it’s poor data management. Nevertheless, the immense repository of records collated in Kliman’s digital variorum presents the scope available to an edition of this kind. While Expanding Lear doesn’t attempt to approach thoroughness of this variety, it ought to suggest formal solutions to problems in presenting the vast resources in controlled fields. Rather than ceaselessly sending the reader into any variety of locations, an expanding edition can present everything on the surface, embedded within the text. This way, entrenched reading habits are maintained while expansive possibilities for deeper investigation are revealed. In its current demo instantiation, Expanding Lear utilizes the widely available Moby Shakespeare (the pervasive internet text adopted from the Clark-Wright 1866 Globe edition) as the primary reading text, with Q1 and F transcriptions (rendered in modern-spelling HTML characters by Internet Shakespeare Editions) as expanding texts.[14] While this selection may seem foolhardy, given the rightly disreputable status of the freely circulating Moby text, it simply represents one scholar’s interest set. In my case, Moby provides a compelling copy for an inquiry into the internet presence of Shakespeare’s work: as first coordinated by MIT, as arranged and investigated by algorithms in Shakespeare Searched or OSS, on Project Gutenberg, or, further afield, as the text is employed in any number of phishing sites hosting Shakespeare to draw in ad revenue from uninformed browsers. Much more than a text of 1866, Moby is an artifact of the early internet. While these questions direct my attention to Moby in direct comparison to facsimile texts and transcriptions of Q1 and F, a proper internet edition ought to allow alternate configurations for divergent attention spans. Thus, with a modicum of markup, the present demo could output the Folio on surface expanding to present, say, Q1 and Tate transcriptions. Or Q1 expanding to Folio and the Pavier Quarto (Q2). Or, more dramatically in light of copyright battles, to host any contemporary conflation expanded with all three (Q1, Q2, and F) or four (Q1, Q2, F, Tate) digital texts. Thus readers can puzzle the nuanced shifts in characterization and narrative among the extant editions for themselves — all while presently aware of the incommensurable texts comprising Lear. As new texts are made available, they can be quickly tagged and dropped into a PHP script generating dynamic choices for the reader. The possibilities are naturally endless, with additions in collation and annotation data obviously essential to various readers. The point is that the reader ought to be able to select a configuration proper to their desired reading (with suggestions available for the general reader). This cross-textual comparison extends to the sidebars. First, in the right sidebar, high-quality facsimile images expand from thumbnail placeholders unobtrusively nested in-line with the surface text. These positions could be tagged to allow appropriate thumbnails for any configuration of texts. With this immediate portal to further ‘unemendation,’ even the casual reader should be apt to fall into an encounter with material text while scholarly users may quickly compare trafficking texts and transcriptions with source images from historical (or contemporary) print publications. Without leaving the site of reading, the user may explore material aspects of the book inaccessible in HTML characters. While the site currently features Q1 images from the Rare Book Room and F images from SCETI/Furness, it also ought to include images from the 1866 Globe edition. Second, in the left sidebar, stable links to all available full text editions of Lear — from 1608 to 2012 in PDF, HTML, or JPG — should be featured to enable focused reading of any particular text. Clearly, this column borrows extensively from the impressive research behind Terry A. Gray’s Chinese encyclopedia Mr. Shakespeare and the Internet. Expansion in this field could draw on resources in EEBO, the Rare Book Room, SCETI and other sites that present multiple copies of a particular edition, thereby allowing for digital collator actions and “stop press” investigations. The task driving a good internet edition is to present all relevant resources clearly and comprehensively. With no additional editing, these circulating texts can be presented in one site, offering a ‘remix edition’ that surfaces the disparate strands of the hive mind for a richer reading experience. Finally, the site features two playful components on the suggestion of Best and the audience of the micro-conference at which a version of this paper was first presented. The first of which, answering Best, is a moving shadow JQuery plugin developed by internet design artists Jonathan Vingiano and Ryder Ripps dubbed “OKShadow.”[15] The script tracks the user’s pointer position within the webpage to simulate a shadow away from the illuminating effects of the cursor. This answer to Best’s call to animate the multiple gives selected variant passages a subtle destabilization that can be investigated in the expanded text.[16] Naturally, any cursory investigation of the expanded field will demonstrate the complete multiplicity of the text in both material and immaterial terms. However, highlighting selected cruxes in this fashion draws attention to conflations derived with greater editorial agency across variant texts. The second component implements the “Annotator” tool developed by the Open Knowledge Foundation currently in use at Open Shakespeare among other locations.[17] Following up on an audience member’s query concerning the user’s potential to interact with the site in a fashion similar to marginal notes in print publications, a small amount of research pointed to a variety of web-annotation devices. While the most helpful of these tools must be implemented by the user (AnnotateIt, for example, is best utilized in a bookmarklet that stores notes across the web), a simple script was embedded in Expanding Lear to enable to the user to keep notes.[18] . . .

Another paper, reoriented with these tools for comparative analysis, might consider the Moby text, measuring its brazen conflation against the various texts from which it draws an edition. These editorial insights might extend to any number of websites that display the text, consciously or unwittingly hosting all the ideological implications one might infer from this or that particular version of Lear. This is not that paper. Nevertheless, it would be apt to conclude, at the very least, by drawing this formal exercise into dialogue with the passage cited in the title: King Lear’s ill-fated demand for a speech from Cordelia to acquire that third more opulent of the kingdom. Yes, in precise verisimilitude, this site responds with the same denial. The internet is full of interpretations of Lear, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more — only to redistribute the texts. In this way, something can, in fact, come from nothing. By reanimating each historical edition as an expanding horizon of unemended digital text, the human reader may find a place to stand in the richness of multiple authority from the vantage of our contemporary textual moment. That is to say:

JW Player goes here

[1] However, these too could be acquired online through Google Books or freely through more legally ambiguous channels. Library.nu, for example, hosts hundreds of PDF and e-book editions of King Lear, up to and including recent Cambridge, Arden, and Folger editions. [2] Michael Best, “Standing in Rich Place: Electrifying the Multiple-Text Edition or, Every Text is Multiple,” College Literature 36.1 (2009): 27. [3] Best, “Standing in Rich Place,” 34-35. [4] Peter Stallybrass and Maria de Grazia, “The Materiality of the Shakespearean Text,” Shakespeare Quarterly 44.3 (1993): 255-283. [5] Best, “Standing in Rich Place,” 36. [6] Of course,

in a variety of locations Best argues for a host of new media actions to

present the multiple, some of which are enumerated in the following pages.

However, “Standing in the Rich Place” can stand symptomatic of both the

inventiveness and short-sightedness of many of these arguments. See, for example,

Best’s “King Lear: Notes Towards a Textual Introduction” on Internet Shakespeare Editions for an

ambitious proposal not entirely dissimilar to many of propositions in this Expanding Lear introduction (though yet

similarly unrealized): http://internetshakespeare. [7] Best, “Standing in Rich Place,” 30. [8] Andrew Murphy, “Shakespeare Goes Digital: Three Open Internet Editions,” Shakespeare Quarterly 61.3 (2010): 414. [9] Murphy, “Shakespeare Goes Digital,” 402. [10] Murphy, “Shakespeare Goes Digital,” 413. [11] Kenneth

Goldsmith, “Being Boring,” http://epc.buffalo.edu/ [12] With more time or resources, this would neither present a challenge in acquisition nor additionally confusion in layout. [13] A challenge

Kilman goes to great pains to address in her introduction to The Enfolded Hamlet: http://leoyan.com/global- [14] Eric M.

Johnson, founder of Open Source Shakespeare, gives a good overview of this

Moby’s digital provenance along with strengths and weaknesses in his

introduction to OSS: http://www. [15] Jonathan Vingiano and Ryder Ripps, “OKShadow,” http://okfoc.us/okshadow/. [16] Of course,

the selected variant passages are not mine, but those highlighted as “major

differences” by Shakespeare enthusiast Dr. Larry A. Brown. See “The Complete

Text of Shakespeare's King Lear with Quarto and Folio Variations, Annotations,

and Commentary,” http://larryavisbrown. [17] Open Knowledge Foundation, “AnnotateIt,” http://annotateit.org/. [18] Unfortunately, these notes currently disappear after refreshing the page. The only way to store permanent notes requires either that the user implement the Bookmarklet on their own device, or save the notes to the page permanently for any user to view. While Open Shakespeare does just this, I’m unconvinced that open collective editing is of any worth without Wikipedia-sized interest groups and user pools. |