an event series at the

kelly writers house programmed by danny snelson featuring editorial practices in contemporary writing t e c h n o l o g i e s

|

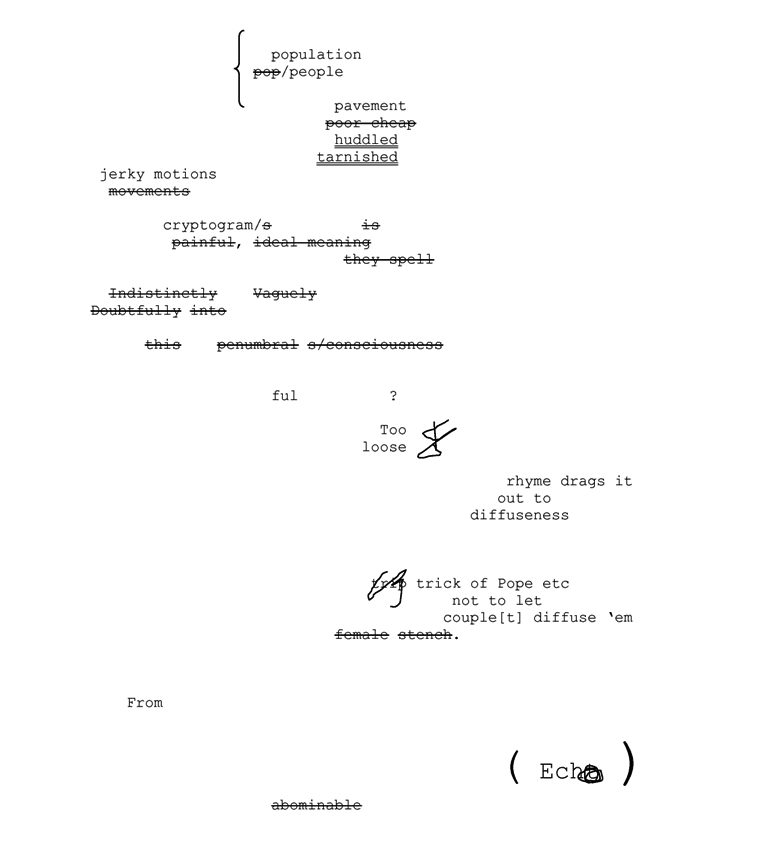

On Morpheu (Blazevox, 2008)

Transmutilation (✝), Crawford writes, has a cleaner, sharper edge. Summoning an oracular arsenal of today's sharpest tools — homophony, algorithmic association, strategic deletion, binary encoding — Morpheu hijacks the legendary magazine Orpheu : a mystical artifact damned to the suffocating underworld of European Modernism, 1915. Recomposing this orphaned journal on federal funds, Crawford's alter-ego Pierrot reverse engineers the industrial ineptitudes of pages lost for readers with such hands as might touch never horrified to look toward the present. Concentrate Pierrot. For the affect is not a personal writing, nor is it a translation; it is the mutilation of a power of the pack that throws the poem into upheaval and makes it squeal. Morpheu seeks not to restore its prey to the land of the living — instead, Crawford plays the perverse puppet-master, reanimating a zombie tranny, a rotted corpus stitched together in full drag. The magazine, like our hero Pierrot, is impaled from the opening on that fated epistolary device — ✝ — an elegant disguise for the 'I' in history. Wait. I don't feel anything yet. / "That's cause you can't seem / to separate yr mythemes / from yr morphemes." — Danny Snelson From political change to pocket change, shipments to shipwrecks, quotations to digital code, Alejandro Crawford never met a morphosis he didn't like, and here in these pages neither will you. Skipping from "omicron" to "omg" to "ominous gold," Morpheu cuts across registers from syllable to syllable, breaking the surface of language to reveal the golden (and sometime ominous) connections between postmodern assemblage and modernist source text (the work is based in part on the Brazilian/Portuguese journal Orpheu , which notably published the work of Fernando Pessoa). The text moves between English and Portuguese, and between the ecstatic linguistic play of Dionysian disruptions and the classical Apollonian concern with measure and a masterfully careful calibration of sound. Here, the two gods of Orpheus vie, and Crawford reveals that in the end, once the dust and tears have settled, they may merely be heteronyms of the same muse. Fragments and pathos: the stones are crying, the limbs tearing — remember the lesson of Orpheus and keep reading: don't, whatever you do, dare to look back. — Craig Dworkin |

|